They look like props from a dream: a gleaming red Coca-Cola bottle, a golden fish, a sleek Ghana Airways aeroplane, a lobster halfway through being painted. Yet these are no mere sculptures, they are coffins. In southern Ghana, the dead are buried in caskets shaped like taxis, Nike shoes, beer bottles, or even cocoa pods. Each coffin, carved with meticulous detail and coated in radiant colour, tells a story of who the person was, and, perhaps, who they wished to be.

A tradition born from royalty and reverence

The tradition of Ghana’s fantasy coffins, known locally as abebuu adekai or “proverb boxes”, originates from the Ga people of the Greater Accra Region. In earlier centuries, Ga chiefs were carried in elaborate palanquins during ceremonies, ornate wooden chairs that signified status and reverence. When a chief died, he was sometimes buried within that very palanquin, a final gesture of dignity befitting his station.

This symbolic link between the palanquin and the coffin laid the groundwork for what would become one of Ghana’s most recognisable art forms. In the mid-20th century, a young carpenter from Teshie, a coastal suburb near Accra, crafted a cocoa pod–shaped palanquin for a local chief. When the chief died before the festival could take place, he was buried in it instead. The striking coffin drew crowds, sparking curiosity and admiration.

Not long after, the same craftsman buried his grandmother in a coffin shaped like an aeroplane, a tribute to her lifelong fascination with the planes that flew over Accra’s new airport. It was an act of affection that symbolically granted her a journey she had never taken in life. That single gesture democratised the tradition, breaking its royal exclusivity and making it accessible for ordinary Ghanaians, allowing everyday people to dream, and to be remembered, in symbols of their own choosing.

The craft of storytelling throug h wood

Today, in the workshops of Teshie and Nungua, artisans still use simple handmade tools to carve fantasy coffins from local wood. Sanding, shaping, and painting are all done by hand. Each piece is designed to represent something deeply personal: a fisherman may choose a fish or a boat, a farmer a cocoa pod, and a barber a hair clipper. Some opt for symbols of aspiration, a luxury car, a mobile phone, even a house.

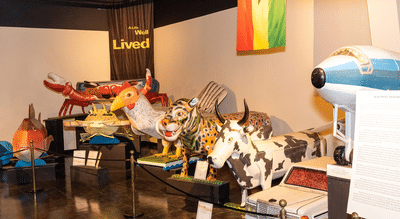

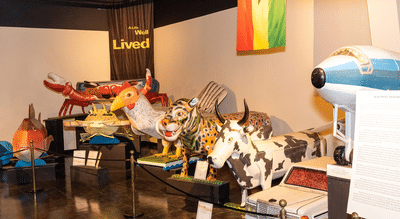

In local workshops, smaller models display the possibilities: syringes for doctors, beer bottles for enthusiasts, trucks for drivers, and houses for landlords. Every design carries meaning, blending humour, pride, and spirituality. For Ghanaians, funerals are not merely occasions of mourning but celebrations of a life well-lived, a “homecoming” marked by music, dancing, and colour.

Coffins typically cost between US$300 and US$1,000, depending on complexity. In a country where many earn less than US$3 a day, such expense is considerable. Families often pool resources or receive community support to afford these custom creations. For some, a fantasy coffin is a final luxury; for others, a symbolic act of respect and love.

Faith, symbolism, and the afterlife

Funerals in Ghana are social events of great significance, where Christian beliefs frequently blend with traditional spiritual thought. The dead are not considered gone but transformed, ancestors who retain influence over the living. A beautiful, well-chosen coffin can help ensure goodwill from the spirit world.

These personalised designs are often aspirational, reflecting not only who the deceased was but also who they might have dreamed of becoming. In a country marked by economic struggle, the coffin can serve as an emblem of pride — a declaration that, even in death, dignity endures. If one could not afford a car, a plane, or a grand home in life, one could at least depart the world inside it.

From local workshops to international museums

What began as a regional custom has evolved into an internationally celebrated art form. In 1989, Ghanaian fantasy coffins were showcased at Magiciens de la Terre, a landmark exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and later at Africa Explores in 1992 at the New Museum of Modern Art in New York. These exhibitions introduced the world to the brilliance of Ghanaian funerary art — merging craftsmanship, symbolism, and storytelling in ways few had seen before.

Since then, fantasy coffins have travelled far beyond West Africa. Collectors and museums in more than twenty countries have acquired these extraordinary works, appreciating them as contemporary sculpture as much as cultural heritage. Yet despite international acclaim, the craft remains firmly rooted in community. Local workshops continue to produce coffins for funerals every week, their vibrant exteriors carried through the streets of Accra in processions filled with drumming, dancing, and celebration.

The living legacy

The fantasy coffin tradition has endured for more than half a century, passed down through generations of artisans. Workshops established in the 1980s still operate today, led by descendants and apprentices who blend old techniques with modern creativity. Though global attention has brought fame and tourism, the craft remains deeply local — a form of storytelling that connects the living and the dead through imagination and respect.

In the end, these coffins are more than curious works of art. They are reflections of Ghana’s enduring belief that life and death are part of a continuous journey, one that can be faced with humour, grace, and a touch of splendour. To be buried in a fish, a shoe, or an aeroplane is not eccentricity; it is philosophy rendered in wood. In death, as in life, the Ghanaians who choose these fantastical vessels make a simple, profound statement: we go as we lived, with pride, colour, and story.

A tradition born from royalty and reverence

The tradition of Ghana’s fantasy coffins, known locally as abebuu adekai or “proverb boxes”, originates from the Ga people of the Greater Accra Region. In earlier centuries, Ga chiefs were carried in elaborate palanquins during ceremonies, ornate wooden chairs that signified status and reverence. When a chief died, he was sometimes buried within that very palanquin, a final gesture of dignity befitting his station.

This symbolic link between the palanquin and the coffin laid the groundwork for what would become one of Ghana’s most recognisable art forms. In the mid-20th century, a young carpenter from Teshie, a coastal suburb near Accra, crafted a cocoa pod–shaped palanquin for a local chief. When the chief died before the festival could take place, he was buried in it instead. The striking coffin drew crowds, sparking curiosity and admiration.

Not long after, the same craftsman buried his grandmother in a coffin shaped like an aeroplane, a tribute to her lifelong fascination with the planes that flew over Accra’s new airport. It was an act of affection that symbolically granted her a journey she had never taken in life. That single gesture democratised the tradition, breaking its royal exclusivity and making it accessible for ordinary Ghanaians, allowing everyday people to dream, and to be remembered, in symbols of their own choosing.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DQKLjsgiEWZ/ https://www.instagram.com/p/DQKLjsgiEWZ/

The craft of storytelling throug h wood

Today, in the workshops of Teshie and Nungua, artisans still use simple handmade tools to carve fantasy coffins from local wood. Sanding, shaping, and painting are all done by hand. Each piece is designed to represent something deeply personal: a fisherman may choose a fish or a boat, a farmer a cocoa pod, and a barber a hair clipper. Some opt for symbols of aspiration, a luxury car, a mobile phone, even a house.

In local workshops, smaller models display the possibilities: syringes for doctors, beer bottles for enthusiasts, trucks for drivers, and houses for landlords. Every design carries meaning, blending humour, pride, and spirituality. For Ghanaians, funerals are not merely occasions of mourning but celebrations of a life well-lived, a “homecoming” marked by music, dancing, and colour.

Coffins typically cost between US$300 and US$1,000, depending on complexity. In a country where many earn less than US$3 a day, such expense is considerable. Families often pool resources or receive community support to afford these custom creations. For some, a fantasy coffin is a final luxury; for others, a symbolic act of respect and love.

Faith, symbolism, and the afterlife

Funerals in Ghana are social events of great significance, where Christian beliefs frequently blend with traditional spiritual thought. The dead are not considered gone but transformed, ancestors who retain influence over the living. A beautiful, well-chosen coffin can help ensure goodwill from the spirit world.

These personalised designs are often aspirational, reflecting not only who the deceased was but also who they might have dreamed of becoming. In a country marked by economic struggle, the coffin can serve as an emblem of pride — a declaration that, even in death, dignity endures. If one could not afford a car, a plane, or a grand home in life, one could at least depart the world inside it.

From local workshops to international museums

What began as a regional custom has evolved into an internationally celebrated art form. In 1989, Ghanaian fantasy coffins were showcased at Magiciens de la Terre, a landmark exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and later at Africa Explores in 1992 at the New Museum of Modern Art in New York. These exhibitions introduced the world to the brilliance of Ghanaian funerary art — merging craftsmanship, symbolism, and storytelling in ways few had seen before.

Since then, fantasy coffins have travelled far beyond West Africa. Collectors and museums in more than twenty countries have acquired these extraordinary works, appreciating them as contemporary sculpture as much as cultural heritage. Yet despite international acclaim, the craft remains firmly rooted in community. Local workshops continue to produce coffins for funerals every week, their vibrant exteriors carried through the streets of Accra in processions filled with drumming, dancing, and celebration.

The living legacy

The fantasy coffin tradition has endured for more than half a century, passed down through generations of artisans. Workshops established in the 1980s still operate today, led by descendants and apprentices who blend old techniques with modern creativity. Though global attention has brought fame and tourism, the craft remains deeply local — a form of storytelling that connects the living and the dead through imagination and respect.

In the end, these coffins are more than curious works of art. They are reflections of Ghana’s enduring belief that life and death are part of a continuous journey, one that can be faced with humour, grace, and a touch of splendour. To be buried in a fish, a shoe, or an aeroplane is not eccentricity; it is philosophy rendered in wood. In death, as in life, the Ghanaians who choose these fantastical vessels make a simple, profound statement: we go as we lived, with pride, colour, and story.

You may also like

Ben Bader cause of death: How did the Miami TikTok star die at 25

UP's 'Viksit 2047' campaign becomes mass movement with 57 lakh inputs

"Should be dismissed..": InGovern Research founder on Washington Post report on LIC

'Learning by Doing' to transform classrooms in UP

Bihar: Foreign liquor seized ahead of assembly polls